The EU Commission published its assessment and recommendations for Ireland yesterday. Here’s the recommendation regarding legal services.

Reduce the cost of legal proceedings and services and foster competition, including by enacting the Legal Services Regulation Bill by the end of 2014, including its provision allowing the establishment of multi-disciplinary practices, and by seeking to remove the solicitor’s lien. Monitor its impact, including on the costs of legal services. Take executive steps to ensure that the Legal Services Regulatory Authority is operational without delay and that it meets its obligations under the legislation, including in terms of publishing regulations or guidelines for multi-disciplinary practices and the resolution of complaints. Improve data collection systems to enable quality and efficiency of judicial proceedings.

And here’s the assessment of Ireland’s legal situation that those recommendations are based on;

The cost of enforcing contracts is high. Lawyer fees represent the majority of these costs, at 18.8 pp and high legal services costs affect the cost structure of all businesses, including SMEs. In addition, unlike for other professional services, legal services costs have failed to adjust downwards since the onset of the crisis, in part due to insufficient competition. The authorities have committed themselves to introducing reforms to the legal services sector as part of the macroeconomic adjustment programme. They published a Legal Services Regulation Bill in 2011 that remains to be enacted. Judicial and court administrative resources to implement active pre-trial case management are very limited, which may be contributing to delays in the delivery of justice and raise costs. In addition, there are significant gaps in Ireland’s ability to collect data on the quality and efficiency of the justice system.

The 18.8% figure (the only statistic cited) comes from the World Bank’s Doing Business survey and is based solely on a single form of legal service- commercial High Court Litigation in pursuit of a breach of contract claim. Strangely, though it seeks to represent the cost of enforcing a contract, the survey methodology doesn’t take account of the fact that our legal system has, as a general principle, that the loser in litigation should pay the costs of the winner.

How are attorney fees calculated?

Average attorney fees are the fees that a plaintiff must advance to a local attorney to be represented in the standardized case. Even though it is assumed that judgment will be 100% in favor of the plaintiff and the plaintiff is likely to be entitled to an award of legal cost along with the judgment, the methodology takes into account all the attorney fees that the plaintiff needs to advance to his attorney, which includes: (i) the fees to handle the case up to judgment, including pre-trial attachment of the defendant’s movable assets, (ii) the fees for enforcement if a lawyer is commonly retained for this purpose, and (iii) if applicable, the value added tax or other taxes.

The World Bank says it hopes to address this, rather significant, lacunae in future surveys.

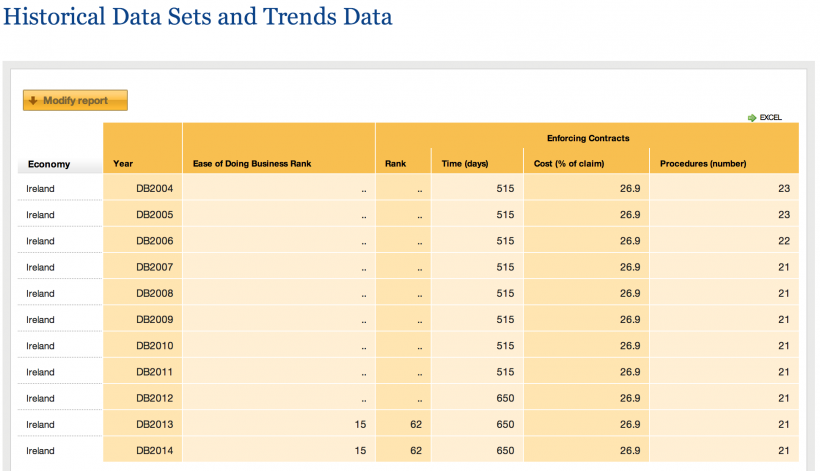

One other curious thing about this figure for costs. I was surprised by the EU Commission’s assertion that “unlike for other professional services, legal services costs have failed to adjust downwards since the onset of the crisis”. Here’s the historical data. Apparently, despite recording changes in both the number of days estimated for completion of the litigation and the number of procedural steps required, the costs have been exactly 26.9% of the value of the claim every single year since 2004.

This is surprising. The Irish Competition Authority found that

“The level of solicitors’ fees in the High Court increased by 4.2% above general inflation annually over the period 1984 to 2003 while the level of senior counsel fees in the High Court increased by 3.3% above general inflation annually over the same period.”

And yet, the World Bank’s figures (and the EU Commission has based its recommendations on those figures) tell us that come 2004, everything suddenly stopped.

I’ve said before I’m barely numerate.

Fortunately, having discussed this on Twitter, Fred Logue had the solution and submitted a EU FOI-style access to information request for the documents the EU Commission used to ground its assertions about the Irish Legal Services market.

We should have an answer by the 23rd June 2014.