There is an excellent article by Elaine Edwards online (but not in the paper) regarding a pensioner whose pension payments have been stopped because she declined to submit to the biometric scanning and so on involved in being given an Public Services Card.

This card has been, to be charitable, inaccurately referred to as voluntary by Minister Pascal Donoghue.

However, if you don’t agree to submit to the carding process (which involves a biometric scan of your face, as well as a system to associate that ID record with your mobile phone) you currently can have any and all your social welfare payments (pension, free travel, children’s allowance, maternity benefit, paternity benefit…) cut off.

In addition, you cannot get a new driving licence, you cannot get a replacement passport if it has been lost or stolen, you cannot get your first passport or be made a citizen.

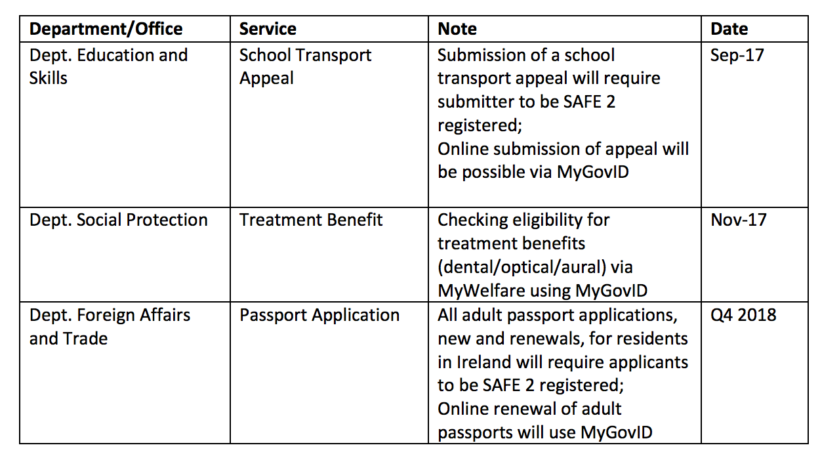

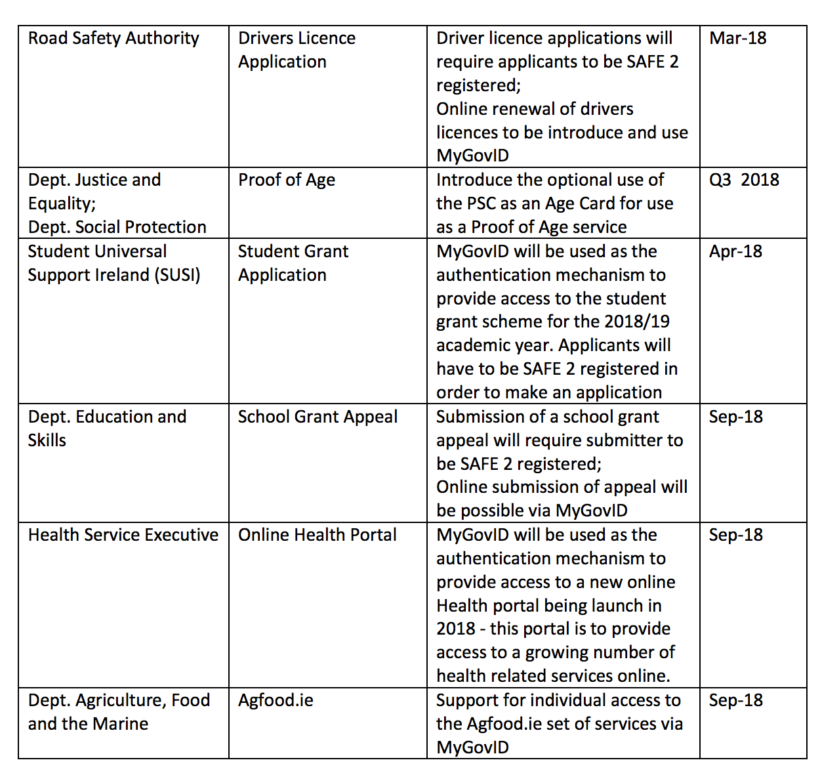

That’s the list of consequences for not volunteering so far. You can read the ambitious list of planned uses on the Department’s own website. I’ve reproduced it below, for ease of reference. Here’s an excellent piece by Loughlin O’Nolan and Elaine Edwards on just how voluntary this system is.

So, what we have here is a national ID card system which has never been debated by the Oireachtas, isn’t based on any primary legislation and has been introduced (where there is any legal justification for it cited at all) by wilfully forcing a new interpretation onto old legislation.

The Legal Basis that wasn’t there

I’d like to just rattle through some of that claimed legal justification, simply to demonstrate how shaky it is. Anyone who has read my previous pieces on the Health Identifiers Act 2014 and the Primary Online Database may notice some familiar themes emerging.

Here’s what the Department of Social Welfare cites as the legal basis for cutting off the pensions of old ladies who refuse to comply with the demand they get an ID card:

The Social Welfare Consolidation Act 2005, as amended, viz.

– Section 247C(1) of the Act provides that the Minister may require any person receiving a benefit to satisfy the Minister as to his or her identity;

– Section 247C(2) of the Act specifies the consequences of failure to satisfy the Minister in relation to identity as required, specifically that a person shall be disqualified from receiving a benefit;

– Section 247C(3) of the Act specifies the manner in which the Minister may be so satisfied; in effect, this Section describes the process for registering a person’s identity

The first two of those provisions simply say that a person who refuses to satisfy the Minister as to his or her identity may have their payments stopped until their identity has been confirmed. This is a completely reasonable and laudable requirement, necessary to make sure money is going to the right person.

But here, the Department hasn’t said that the lady whose pension they’ve stopped isn’t who she says she is. They’re not denying her identity at all- they know who she is. An official even visited her at her house and was shown her marriage cert. The lady has produced her passport- the document which Ireland expects every other country in the world to be an acceptable proof of identity at their borders.

Again, they know who she is. That’s not why they’ve cut her off. They’ve stopped her pension because she refuses to comply with the biometric carding process.

And for that, they’re relying on Section 247C(3) of the Social Welfare Consolidation Act 2005. The actual provision was only brought in in 2013 in the Social Welfare and Pensions (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2013

The problem for the Department is that, though Section 247C(3) describes a visit to a Social Welfare office, showing some documents and having your picture taken and giving a copy of your signature as being the Minister’s preferred method of you proving who you are, it doesn’t say that the purpose of doing so is to have your data entered onto the national Public Services Card register, with all the subsequent data sharing and processing that involves.

The Act sets out, in a clause not cited by the Department, that this attendance and these records can only be lawfully used for one purpose. Section 247C(1):

“to satisfy the Minister as to his or her identity”

Once that’s done, there is no lawful basis for any further use of that data. No legislative requirement to be placed on an ID register. No basis for sharing the data collected with other government agencies (as envisioned by Section 8 of the Health Identifiers Act, for example).

Joan Burton, when she was Minister for Social Protection, acknowledged that building an ID database was something which couldn’t simply be treated as an administrative act. It has serious and permanent consequences for the relationship between the citizen and the state.

The question of the introduction or otherwise of a national identity card was not part of SAFE’s remit. The matter of establishing a national identity index and producing a national identity card is a wider issue. It would require due consideration by the appropriate agencies before any policy decisions could be formulated by Government and would require the development and implementation of legislation to support any such policy. (source)

Now, you can issue a person with an ID card without a legal basis, if they consent to it. Of course you can. The problem is, in order for that consent to be valid under EU law, it can’t have been compelled. It can’t have been extracted on pain of penury at the loss of your pension, of the child benefit you rely on or your unemployment benefit.

And a person can’t give consent if they haven’t been clearly told to what purposes the data they are agreeing to hand over will be put.

Until we have a full and open debate on the merits of a national ID card (and the identity index database those cards extend from) we cannot decide if we are happy with the consequences of such a plan or (as happened in the UK) whether we decide it is a dangerous and illiberal step.

If the Government wants to legislate for an ID card, let it first propose the plan and see it through the Oireachtas.

Personal data is legitimately gathered and used by the state on the basis that it is a safe guardian of citizens’ fundamental data and privacy rights. Without trust that the state will do the right thing, the legitimacy of that collection breaks down.

If the state won’t even admit to what it is doing, how does it expect citizens to trust that it will do the right thing?